S .F. painter’s ultra-vivid portraits convey character

Sometimes David Tomb is a little startled when he walks into his studio and encounters his life-size portraits of friends. “It really feels like the person is there,” says Tomb, a noted San Francisco painter whose boldly colored pictures draw on the long tradition of portraiture but have an edgy contemporary buzz of their own.

Sometimes David Tomb is a little startled when he walks into his studio and encounters his life-size portraits of friends. “It really feels like the person is there,” says Tomb, a noted San Francisco painter whose boldly colored pictures draw on the long tradition of portraiture but have an edgy contemporary buzz of their own.

Tomb hopes that visitors walking into the Hackett- Freedman Gallery will experience that same “split second of suspended disbelief,” when the people in the paintings appear alive and present. He likens the sensation to confronting a diorama in a natural history museum, when what’s real and what’s not momentarily blur. That’s why Tomb calls this show “Diorama.” It comprises just four big portraits, one of his wife and the others of close friends well known in Bay Area music and art circles: musician Cory McAbee of the Billy Naylor Show, artist Steven Briscoe and performance artist Steven Raspa. They go on display in the small back gallery at Hackett-Freedman tomorrow night, the first Thursday of the month, when downtown San Francisco galleries stay open late for show-hopping crowds.

These paintings, whose thickly impastoed faces and hands suggest the influence of Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, are more formal and controlled than the wildly gestural figurative drawings and paintings for which Tomb is best known.

These paintings, whose thickly impastoed faces and hands suggest the influence of Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, are more formal and controlled than the wildly gestural figurative drawings and paintings for which Tomb is best known.

“I think these are a little more refined,” says Tomb, 39, a Bay Area native who studied at Long Beach State and whose unorthodox portraits were the subject of an exhibition earlier this year at the Fresno Art Museum. The drawings “tended to be a lot more gestural and layered, and a little more improvised. There was a lot of exploration and invention, and I feel a lot of that is still happening in these, but it’s a little more subtle.

“For me it’s important to have a balance of refinement and aspects of the picture that are little more rough and tumble or less developed. Over the last few years I’ve been more focused on color, using vibrant color, sometimes even aggressively, as a really strong component of the picture.”

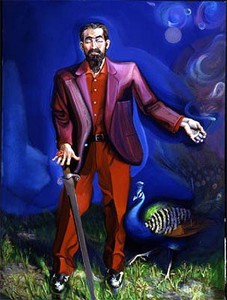

These pictures rock with blazing reds and greens, blue and yellows, befitting the flamboyance of some of these showbiz folk. Performance artist Raspa, known for his “Burning Man” installations, stands in a purple blazer and fire-red shirt and trousers. That’s what he wore while posing for the picture during numerous sessions. But his eyes weren’t closed, as they are in the painting, nor was there a peacock at his feet, or that great swath of blue behind him.

While Tomb depicts his subjects with a certain verisimilitude, he reworks the image for as long as two years until the portrait emerges. He places the figures in fictional settings whose contrasting forms, colors and textures create tension and say something about the subject. The painting is not just a portrait of the sitter or of himself, but “that dynamic between us,” Tomb says, “the connection between the two, the friendship or the energy, for lack of a better term, or communion. I guess it’s a document of what happens in between.”

After the sitter leaves, Tomb starts to invent, adding and taking away elements that bring out the strong presence of character that “I like to think all my friends have,” he says with a laugh. He finds their particular characters “elusive and mysterious. It’s something I want to share with other people.”

He repainted Raspa’s eyes shut because he wanted to portray his friend’s dreamlike quality. The peacock just came to him and felt right. “Steven has a very intense and vibrant spirit. The peacock is a very exotic bird, and there’s also something slightly menacing about it. It’s beautiful and menacing. Steven is not really a menacing person, but there is a bit of an edge to his personality. There is something just slightly menacing about his face, but balanced with a kind of wonderment. It’s those tensions that to me are really interesting.”

Tomb’s portrait of Briscoe, with his neon-green blazer and red electric guitar, is loosely based on Manet’s “Luncheon in the Studio,” except here the bountiful meal is replaced with a huge bottle of Bass ale.

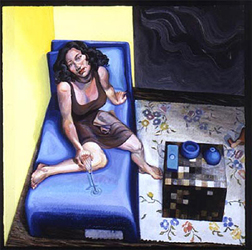

Tomb portrayed his wife, Susan, sitting on a settee in a compressed living room space where objects have been tilted up to the picture plane in a way that makes it seem “vertiginous and flat at the same time,” Tomb says. Holding an empty champagne glass, she has a melancholy expression that her husband attributes half-jokingly to “sitter fatigue.” Tomb thinks the picture captures Susan’s introspective nature. “My wife is a lot more beautiful than how the picture turned out,” says the artist. “But there’s something about how it came out that is very much Susan.”

Portrait painting is hardly hip in the contemporary art world. But Tomb, whose grandfather was the California Impressionist painter Sidney Lemos, likes being part of a tradition to which he feels he’s adding something new and subtle of his own.

“Some people find it constricting and confining. But I happen to find it very rewarding. Most of the great artists I’ve been inspired by have done portraits — Picasso, Modigliani, Caravaggio, Velazquez, de Kooning. For me it seems like such a natural thing. People’s faces are very compelling and interesting.”