While growing up on an Oakland hillside, artist¬†David Tomb¬†‚ÄĒ his last name is pronounced ‚ÄúTom‚ÄĚ as in ‚ÄúTom Sawyer‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ was interested in both art and birds. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm not sure which interest came first,‚ÄĚ he muses. The home where Tomb grew up was filled with landscape paintings by his grandfather, the California Impressionist Sydney Lemos (1892 ‚Äď 1944), and he remembers being fixated on the texture of a painted redwood tree in one of them. On the other hand, there were often turkey vultures sunning themselves in an oak tree behind the house, and they were at least equally fascinating.

‚ÄúI was a bird nerd kid,‚ÄĚ says Tomb. Accordingly, he spent many hours with his nose in vintage bird books including the field guides of Roger Tory Peterson (1908 ‚Äď 1996), and numerous illustrated books by the American ornithologist and artist Luis Agassiz Fuertes (1874 ‚Äď 1927). Fine art was a kind of parallel fascination, and although 18-year-old Tomb did a few bird drawings at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, art was about something else; at least it started out that way.

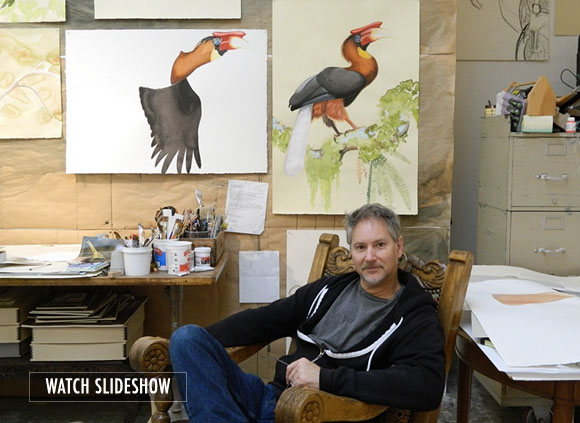

David Tomb

While attending Cal State Long Beach as an undergraduate, Tomb studied drawing with John Lincoln, who in turn was a student of the figurative expressionist Rico Lebrun (1900 ‚Äď 1964). Not surprisingly, Tomb also used the figure as his main artistic vehicle. After earning a bachelor‚Äôs degree in fine arts in 1984, Tomb returned to the Bay Area where his work consisted mostly of portraits, including many of friends who would drop by his studio.

As a portraitist, Tomb demonstrated tremendous persistence, developing a practice in which drawing played a key role. ‚ÄúTomb uses his subjects‚Äô appearance to get his hand going, not as inroads to their character,‚ÄĚ is how critic Kenneth Baker put it. In one memorable sequence executed between 1985 and 1991, Tomb, who does not do commissioned portraits, made several hundred drawings and about 50 paintings of ‚ÄúRichard,‚ÄĚ a high school friend. Writer Bruce Nixon detected in Tomb an artist who was ‚Äú…always testing the breadth and depth of what he knows or is willing to consider.‚ÄĚ Another key aspect of Tomb‚Äôs artistic approach ‚ÄĒ which counterbalances the artist‚Äôs hesitations with his moments of clarity ‚ÄĒ is that he clearly wants his viewers to join him in the arduous process of ‚Äúscrutinization.‚ÄĚ To put it another way, Tomb is an engaged artist who encourages engaged viewing.

Although a few images of birds cropped up in some of his paintings of the late ‚Äô80s, Tomb avoided using them as primary subject matter, despite his continuing hobby of ‚Äúbirding.‚ÄĚ Because he is ‚Äúnot a fan of pet birds,‚ÄĚ Tomb remained unsure how he might properly observe them, and render their particulars. Then, in 2004, several friends simultaneously challenged him: ‚ÄúDavid, when are you going to do bird paintings?‚ÄĚ Realizing that he had been given a ‚Äúsignal,‚ÄĚ Tomb tentatively returned to the California Academy of Sciences, and got a pleasant surprise as he began to again draw specimen birds. ‚ÄúI had a great time,‚ÄĚ he recounts. ‚ÄúEventually those studies became the basis of birds in paintings. It all came together naturally.‚ÄĚ

With ‚Äúbirder‚ÄĚ friends, Tomb had begun making pilgrimage to seek out rare specimens in their native habitats. In the early ‚Äô00s there were trips to Mexico and South America, and by 2008 Tomb had begun to publicly exhibit bird-themed works beginning with an exhibition titled ‚ÄúTreasures of the Sierra Madre: Birds of West Mexico.‚ÄĚ

In January of 2011, Tomb set off on a trip that was was a life-changing experience: a visit to the Philippine island of Mindanao to observe the Philippine Eagle. Spurred by the lingering impressions made by plates of the ‚ÄúPhilippine Monkey-eating Eagle,‚ÄĚ in his childhood copy of¬†Eagles of the World, Tomb was hoping to experience what he characterizes as ‚Äúone of the most coveted of all bird sightings.‚ÄĚ

The Philippine Eagle is considered critically endangered, with as few as 200 adult birds now surviving in four island habitats. Tomb‚Äôs expedition took him to the southern island of Mindanao, then to the city of Cagayan de Oro, then to the tiny village of Dapitan where his gear was loaded onto water buffalo for the trek up a muddy gully to the lodge ‚ÄĒ a ‚Äúfunky old shack with bats and rats.‚ÄĚ

On the first day of birdwatching all that Tomb and his friends saw was rain, but on the second day eagles appeared. Huge, shaggy brown and white birds with distinctive crests ‚ÄĒ Tomb says the crests remind him of lion’s manes ‚ÄĒ the eagles can weigh as much as 18 pounds. It was a ‚Äúhuge thrill‚ÄĚ to see the birds, Tomb says, comparing the experience to ‚Äú…going to Rome and seeing a Caravaggio; a beautiful special thing of rarity.‚ÄĚ

David Tomb, ‚ÄúGreat Philippine Eagle,‚ÄĚ 16¬ĺ √ó 22¬Ĺ inches. Archival digital limited edition print from an original watercolor/gouache

Then, after a successful quest for beauty, Tomb took in the downside. The Philippine Eagle, which Tomb describes as ‚Äúiconic, like the panda or the tiger,‚ÄĚ might not be around much longer. Deforestation, the presence of pesticides, mining, development, and poaching are all taking a serious toll. Before leaving the Philippines Tomb visited the¬†Philippine Eagle Foundation¬†in Davao where some 37 eagles ‚ÄĒ many of which have been injured and cannot return to the wild ‚ÄĒ are being used in a breeding program. On the night that Tomb‚Äôs party arrived a badly wounded adult eagle arrived. It needed emergency surgery to remove one of its wings, and the next morning Tomb‚Äôs friend Peter Barto solemnly took video of the giant maimed bird, wrapped in gauze, blinking its eyes as it came out of anesthesia.

Another sobering moment came when the group visited a defunct logging concession near the town of Bislig on Mindanao. There, they came across a vast, open, treeless landscape. The view included ‚Äú…charred waist high tree stumps of smallish to medium girth and a few random very large stumps of what was the few old growth trees that survived the first clear cutting some forty to fifty years ago.‚ÄĚ Tomb‚Äôs guide then explained that just a few months before, at the same site, he had observed a very rare Rufous-lored Kingfisher in a healthy second growth forest. ‚ÄúNow there was no Kingfisher and no forest,‚ÄĚ Tomb laments.

Upon their return to California, Tomb and his friends reflected on their trip and realized that it had been a call to action. Together with Peter Barto, Howard Flax, and Ian Austin, Tomb set up¬†‚ÄúJeepney Projects Worldwide: Art for Conservation,‚Ä̬†an organization devoted to raising funds for the Philippine Eagle Foundation, and to educating the wider public about bird conservation in general.

Tomb‚Äôs personal webpage now has a section entirely filled with his bird-themed works of the past few years. Spread across the page are paintings of an Eared Quetzal, a Great Kiskadee, an Emerald Toucanet and many other rare creatures. The birds are rendered in stunning detail, and Tomb‚Äôs expressive line has tightened up to better suit the realism required by his new subjects. At the very top of the page, reigning like a king, is a Philippine Eagle. More than any other, this particular bird ‚ÄĒ through its majesty, its rarity, and its beauty ‚ÄĒ has opened up a new phase in Tomb‚Äôs artistic career. Somehow, an artist‚Äôs search for rare beauty brought him towards responsibility, a beautiful thing in itself.

Beginning on Feb. 2, Tomb‚Äôs installation ‚ÄúThe Bone Room Presents‚ÄĚ in Berkeley will feature works on paper depicting not only the Great Philippine Eagle but also other rare and beautiful endemic birds of the Philippines, including the Rufous Hornbill. There will be living plants and an audio installation that will highlight sounds of the Mindanao jungle. The exhibition is meant to shine a light on the rare and beautiful birds of the Philippines and also to communicate the challenges and tensions these creatures face in order to survive and share a sustainable future with an ever growing Filipino population.

‚ÄúMaking artwork of the birds is a way to connect and personalize my experience of seeing¬†the birds.‚ÄĚ Tomb relates.‚ÄúThe ultimate goal is to have people think: ‚ÄėThat animal is incredible.‚Äô‚ÄĚ

***

Jeepney Projects Worldwide: Vanishing Birds of the Philippines

An Exhibition and Installation by David Tomb

Audio by Flip Baber and Johnny Random

Feb. 2 – 29

The Bone Room Presents

1573 Solano Avenue, Berkeley, California

Artist Talk by David Tomb: Thursday, Feb. 23 at 7 p.m.